part 2

sheetmusic

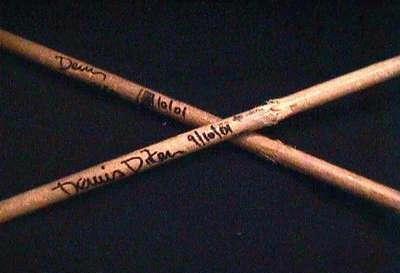

Legendary Smithereens drummer

Dennis Diken's

complete liner notes

from the actual CD booklet"In Search Of An Editor"

Some of his fans are rabid in their quest for every uttered morsel he has plopped onto magnetic tape. Radio dial surfers have been mystified when stumbling onto some of his more wacked-out cuts aired on adventurous college stations. Then there are those who harbor a fuzzy recognition of his literary-sounding moniker from dog-eared reviews or yellowing blurbs in the press. During his thirty-plus years of unleashing his sounds upon the world, R. Stevie Moore has lurked and hulked in far-flung corners of mythical, musical godhead.

We are not here to dispel any well-honed lore of this revered cult legend. Might we attempt to "figure out" the sometimes strange, other-time classic work of R. Stevie Moore? Can we hope to uncover just what it is that makes the man tick? Balderdash! Here is a task this writer would not wish upon his lowliest of chump chums. Just what is it we are doing then? We are attempting to shine a ray of light into the inner sanctum of the enigmatic Mr. Moore. We hope to get a sense of from whence he came and to get to know him just a little better. To know Stevie is to . . . well, love him. Yours truly does, anyhow. Hopefully, after digging into this package, you will too . . . if'n you don't already, that is.

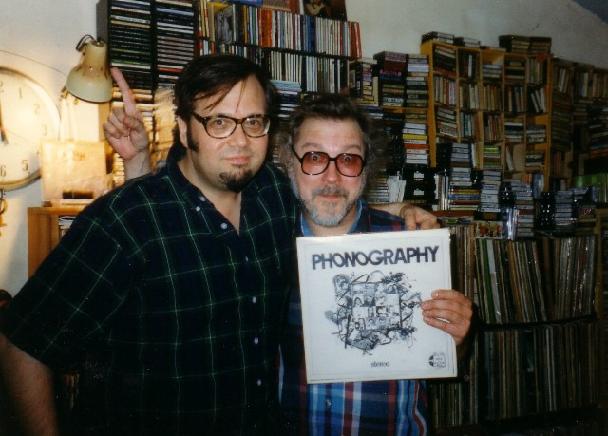

I had the rare pleasure of spending a few three hours with the reclusive R. Stevie and Krys O in Moore's record / cassette / videotape-buttressed, smoke-filled attic apartment in Montclair, NJ, on August 25, 1997. Stevie, the human musical knowledge encyclopedia, was quick to point out that the date of our meeting was the birthday of Elvis Costello. There are pockets of avid music fans throughout the world who hold Stevie with the same high regard as the bard McManus.

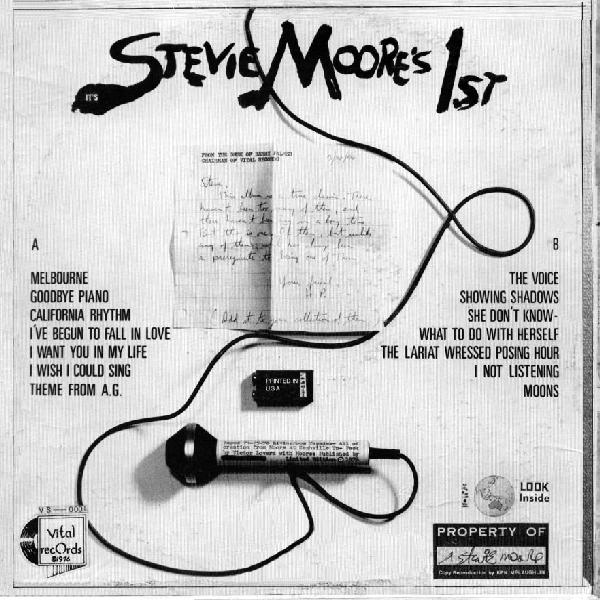

Though his recordings are not as readily commercially attainable as E.C.'s, Moore has made his prodigious output available through his 20 year old homegrown cassette club, and wise labels across the globe have bestowed limited pressings of his LPs, 45s, and/or CDs to the world. The number of titles released on these combined formats totals 18 [plus the 230+ titles available through Stevie's Cassette Club]. It all began with Phonography.

But where did Stevie begin? As the artist announces in his own words on cut #2 on this CD, he was born on Friday, January 18, 1952, and grew up in Nashville, Tennessee. His dad is Bob Moore, probably the most legendary and widely recorded bassist in "Music City" during the '50s through the '70s. His groove was integral to thousands of cuts recorded (and billions of records sold) during that era. Artists like Roger Miller, Roy Orbison, the Everly Brothers, Elvis Presley, Patsy Cline -- to name a smidgen -- they would wait for an opening in the Senior Moore's calendar before booking a recording session. Bob even scored an international hit in 1961 under his own name with "Mexico" (composed by master scribe Boudleaux Bryant), a Mariachi-styled instrumental that purportedly inspired Herb Alpert and his Tijuana Brass to to their thing. (Incidentally, this record was released on the successful Monument label, of which Stevie's dad was a co-founder/owner with Fred Foster.)

Stevie cannot recall a time in his life when the strains of tunage did not grace his cranium. Though his talent must be the result of some fantastic genetic engineering, the ubiquity of melodies in the Moore household probably didn't hurt none when it came to easing him on down the musical road. He began his lifelong addiction to all things vinyl in his toddlin' days and he dug it all; his Dad's avant garde and West Coast jazz LPs, hits of the day, promotional 45s that advertised the local store, comedy albums, etc. This varied palette of platters expanded his vistas and the consumption thereof stirred the boy's creative juices into a frenzy.

"My mom was seventeen when she had me. My dad was nineteen. So I went through that whole thing growing up, having, you know, super-young parents. And with my dad so successful, they were like [snaps his finger], the hippest of the hip, right? Big bucks, swimming pool, going to Elvis sessions, flying to Honolulu. In some was I ate that up, and in some ways, you know, I had no clue about any of it. [I had] a very abusive childhood too. So maybe that has a lot to do with this Phonography stuff, who knows? Obviously it's got to be in there somewhere.

"I've even gone through decades of either trying to ride my father's career to help me get farther, or I've just said, 'well, I'll have nothing to do with it.' Often people think I'm Scotty Moore's son and I've played with that!"

At the age of seven, young Moore made his recording debut as a guest boy vocalist on Jim Reeves' single "But You Love Me, Daddy" (a posthumous U.K. hit for Reeves ten years later in 1969!). This was an assignment of some irony, considering the strained relationship that Stevie and his father endured. Like his old man, he picked up on the bass guitar and in time found himself employed as a session man. Though the bulk of his work centered on cutting demos, he may be heard holding down the bottom on Perry Como's 1973 RCA 45, "Love Don't Care" (produced by Chet Atkins at the legendary RCA Studio B), and he appears on the soundtrack to WW and the Dixie Dance Kings (one of those Burt Reynolds and Jerry Reed extravaganzas). Completists might like to hear his lead guitar on the Manhattans' rockin' soul cut "Teenage Liberation" on the Million to One LP on the King/Deluxe label.

In 1968, while in his junior year of high school, Stevie began unwittingly carving out his life's work as a home recording monk, learning and honing his DIY craft as he went along. He describes this early stuff as "basic, although it's charming as can be in a certain way, but it's pretty unfinished. Some of it was band recordings, some just Mothers of Invention 'toilet music.' Some 'sound on sound,' some tape manipulations, some splicing, the whole gamut."

By 1972, his writing and recording prowess was starting to peak. The playing of all instruments on the original Phonography album is by the hand of the artist. He lived with a girl who paid the rent while he eked out a meager income from sporadic session work and hawking songs for his dad's "little, tiny, minor league, in-house catalog publishing company. At some point he was paying me to go out and knock on doors. I hated it. It made me uncomfortable because they had to turn me down, even though I was 'the legendary Bob Moore's son.' Then I would come home, smoke a joint, and get under the headphones and record.

"The 'Nashville Period' was a whole different thing because it was just out of nowhere. It was desperation, not having any idea of any future. This stuff [the music] was just pouring out of me. There was no New Jersey to come to. I was jus there, stuck making music that sounded like my idols. Who down there could care about Brian Wilson or Roy Wood or 10cc or Roxy Music or Sparks, all the things I was listening to . . . of course, Beatles and all the common stuff. Outside of my small circle of friends who liked the same stuff that I did, there was the typical Southern Rock/Allman Brothers thing happening. We hated it. In retrospect, now that I look back, some of that stuff's really great -- a lot of it's not so great. Charlie Daniels I knew when I was this tall. When I was doing pop music, I hated that kind of . . . riffery, and blues, and country-ish stuff.

"It's difficult, in some ways, to tune back to that era. What was I thinking and what was I going through and what was I up against? I hardly remember those days. Nobody understood what I was doing except for my friends and my uncle."

That uncle is one Harry Palmer (Stevie's mother's brother), of Wayne, NJ. A guitarist who had cut his teeth in the Boston folk scene of the '60s, he had previously been a member of Ford Theatre (who released two pop-art LPs on ABC Records in the latter part of the decade). He dug what R. Stevie was putting down and became a sort of patron of the art to his talented nephew, encouraging him to send him copies of whatever he committed to tape. He hand-picked his favorite RSM tracks from the '72-'74 period and compiled them into what became Phonography. As such, the album is not a preconceived work.

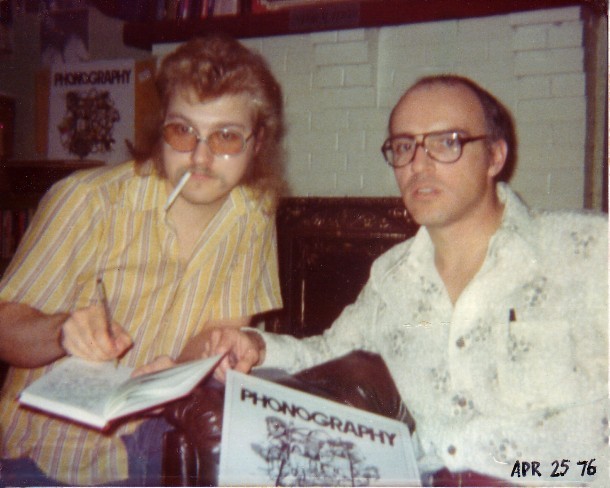

Sunday 25 APR 1976

The original LP was issued in July of '76 in an initial run of 100 copies on Stevie's own Vital label. It was later reissued with different cover art in 1979 on HP Music.Looking and listening back, the music of the Phonography era might be viewed as the sound of Stevie clawing his way out of the confines of his enclave within his despised Nashville. Yet all the while he was having a ball, tinkering with the craft.

"All of the songs had the same kind of story as far as the general recording of what I was doing and my lifestyle at the time. None of these things are based on any intense love or hate relationships. In some ways they're almost third-person even though I use the word 'I.'" In some songs the images are subliminal with cryptic lyrics. Others are decidedly literal, sometimes childlike. Stevie coined it best when reminiscing about Phonography: these tracks are "quintessential R. Stevie Moore."

The instrumental "Melbourne" puts Stevie's childhood piano lessons to good use. "It was just a piece that started out one of my tapes and at that point it was like the best thing I'd done, and Harry loved it and chose it to open the album."

"Explanation of Artist" is excerpted from a series of "narratives" that Uncle Harry commissioned Stevie to wax. "Harry always loved my speaking voice and . . . he even paid me to talk into the mic [and] send tapes of just me talking. So there's gobs of "Explanation of Artist." A lot of it is just, you know, totally ridiculous without any kind of context, and a lot of it is brilliant, you know, whatever. The whole thing is called The Voice [available as part of NT19 from the Cassette Club]. Harry picked and chose the little pieces that are on Phonography. But they are much longer."

Other bits from The Voice pop up throughout the album: the dude demonstrating his guitar method preceding "Theme From A.G."; the C-Span-like talking head on "The Lariat Wressed Posing Hour," and the condescending record company exec on "Mr. Nashville."

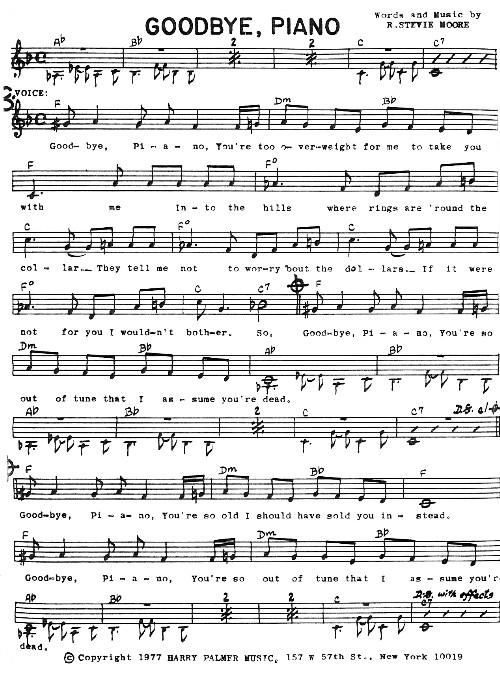

"Goodbye Piano" is a farewell to a faithful old out-of-tune upright that dwelled with R. Stevie during one apartment residency that ended in '75. It was also one of the songs that comprised "Four from Phonography," an EP that Harry compiled and released in December of 1977, right before Stevie's move to New Jersey. Fellow avants the Residents dug this sampler, and this mummer Bay Area outfit became kindred spirits with the RSM camp.

Stevie and his West Coast comrades were championed by Trouser Press, the cultish Anglophile music mag through which many fans discovered Phonography and other seminal RSM works, by reading glowing reviews by the likes of Kurt Loder, David Fricke, and Ira Robbins. Harry and Stevie plied issues of the periodical with clever teasers and larger ads for upcoming releases. In one case, Moore promptly grabbed a letter of praise from the Residents and paid good money to see it splashed as a full-page, inside back-cover ad in one issue!

Similar to this paper chase, the practice of "recycling" pre-existing audio material within his work (be it phone messages, or verite recordings like the rah-rah-ing of the cheerleaders from his alma mater, Madison High, outside his window) was to become a common trait of the diarist known as R. Stevie Moore.

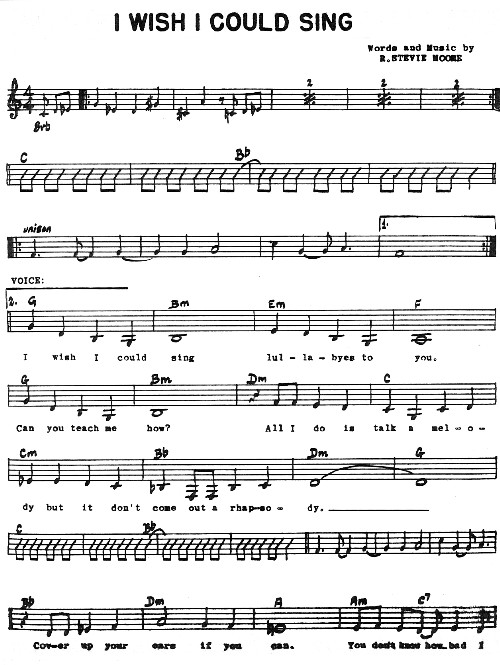

R. Stevie makes no bones about wearing his influences on his sleeves. "Goodbye Piano" and "She Don't Know What To Do With Herself" sound Sparks-inspired. "Another Day"-era McCartney resonates in "I Want You in My Life." Roy Wood (ex of the Move, Wizzard, and the first ELO album) released Boulders in 1973, an album on which he plays all of the instruments. A bunch of Stevie's stuff smacks of Wood, "I've Begun to Fall in Love" and "I Wish I Could Sing" in particular. The Mothers of Invention are all over this stuff. "I bought Freak Out and Absolutely Free at Sam Goody's at the Bergen Mall when I was visiting my grandparents in New Jersey during the summer of '67," says Stevie.

Following the pilfered version of "My Country 'Tis of Thee" and the Casey Kasem radio spot lies "California Rhythm," a prime example of Stevie's innamore with Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys. The sound glitch on this number was not intended as an artistic statement. It is a screw-up.

"Explanation of Listener" emanated from a found piece of reel-to-reel tape, acquired by Stevie from an acquaintance who worked at a company that produced public service programs. The identity of the original commentator remains unknown. The obvious "concerned citizen" is Our Stevie.

"All of my tapes were radio show-like anyway. There were always little bits in the links and stuff like that. It wasn't just pop songs." When Stevie mentions "my tapes," he is referring to the multitude of completed "albums" as such that he was sending his Uncle Harry on reel-to-reel tape. "I was overloading him. The story of my life, the quantity outweighing the quality. I never really sent him a new tape of two or three tracks that I think are, you know, really gonna grab you. It was always 'here's my new double album.' Next week, 'here's another double album.' The story of my career. I need an editor."

An editor was not employed for the preparation of this compact disc edition of Phonography. To the contrary, a whopping nine bonus tracks adorn the original program. These recordings hail from the same "Nashville Period." ("Dates" dates back to '73 and features Stevie's schoolchum and bandmate Billy Anderson on fuzz bass -- a rare guesting on an RSM session. Billy also twirls the tambourine on "Melbourne.")

Basically, these numbers are yet more quintessential R. Stevie, from the pure pop of "You and Me" (vintage 1975, during what Stevie claims to be one of his peak years) and the Merseybeat-ish "Why Should I Love You," to the pronounced Wild Honey and Friends-era Beach Boys flavor in the stream of consciousness of "Wayne Wayne Go Away." Typical Moore frivolity prevails in "Forecast" (inspired by a Nashville weather man), and "Topic of Same" has that familiar Roy Wood vibe.

"Because We're the Dig" was composed by one Victor Lovera (as pictured with Stevie on the photo booth shots on the original Phonography cover), a fellow who is worth noting in the story of R. Stevie Moore. "In '71 . . . I moved out of my house . . . away from my parents, got a little room and was free at last. In the next room I heard this singer/songwriter guy. And he was from Long Island, New York, somehow down in Nashville. He was arthritic, had a cane, long black hair. He became one of my best friends and, you know, very influential for my songwriting. He was like a Paul Simon, Cat Stevens, James Taylor . . . we're talking '71 here, you know. Him and his acoustic guitar. Real strange character, chess player, brilliant cat, a real renegade. He was always, like, a genius talent that really inspired me a lot. We worked together through the '70s. Even did a lot of recordings that parallel these recordings . . . where I was his band. He's doing guitar and vocals, he was a great singer, a great writer . . . very McCartney-esque. And he's still trying to do it to this day. He's back out on Long Island." He currently performs in a band called Those Guys. (Interestingly, John Hiatt was once a housemate with RSM and Lovera in Nashville.) Sadly, Vic passed away in May 1998.

"Hobbies Galore" (one of Stevie's self-proclaimed "greatest hits"), not unlike most of his works, is not inspired by one thing in particular. Nonetheless, the title is a nod to the life of R. Stevie after the whistle blows at the end of the day. "It sums up my career," says he. Recording artists, musicians, and songwriters of all ages (not to mention purveyors of the current-day "low-fi" movement) would do well to observe RSM's modus operandi of creating these tracks. As for the writing, the music generally came first with the lyrics and melodies following. Most cuts were completed the same day they were started.

The guitar of choice on most of these recordings was a red plastic Hagstrom affair. It was not his first nor his last axe, and no, he does not own the thing any more. Almost always, it was plugged directly into the machine, though effects pedals were often employed. The electric bass (which is the instrument that Stevie is probably most proficient at, and with which he is most associated) was a Fender Precision.

The drums were invariably added last. R. Stevie's playing bristles with personality and imagination, easily complimenting the man's vision for the cut at hand. Mind you, a full kit was seldom used. Generally, he wrapped a chrome Premier snare and a hi-hat (both picked up on one microphone) and sometimes a bass drum was not kicked. It may have been approximated by another element -- sometimes a big damn cardboard box.

The striking sounds and evocative textures heard on Phonography were created by the utilization of two quarter-inch quarter-track sound-on-sound tape machines, bouncing mic line inputs back and forth between both devices. In so doing, Stevie had to decide what was going to be locked in on the final musical picture as he went along in the recording process. In other words, he was mixing as he worked. Consequently, it became necessary for him to keep the level high on the first part recorded, in order for it not to be obscured by the parts that would subsequently be overdubbed. He was able to stack sound layers on top of one another (fifteen being the approximate maximum number of overdubs piled at a given time), but without the luxury of a fidelity-preserving multi-track format, the sonic picture may take on a squashed and sometimes surreal quality. This unusual feel is not uncommon on many home recordings of the era.

Stevie worked with one "real cheap" Sony cardioid microphone (in the $15-30 range -- see the cover photo). Headphones always served as monitors. No noise reduction was available, and, remarkably, no tape hiss impedes the listening experience. When asked why this is the case, Moore replies "I don't even know how I did it. I've gotten a DAT machine and a Portastudio and I still haven't been able to re-approach that mentality of 'I'm just gonna keep going.' I'm always afraid of . . . I don't wanna make it sound bad. And after a while you do start to make it sound bad."

Contrary to popular belief, R. Stevie Moore has seen the light of day. He has occasionally emerged blinking from hunkering down in the confines of his four walls to perform live. He once even played with the Earl Scruggs Revue, and performed as a sideman on the Grand Ole Opry! One RSM band that played originals was called Ethos [See NJ63, NT78, NT89, and NT139]. In 1976 he and some high school buddies formed a cover band called the Swings [one of their shows is preserved on NTK136; another gig backing the coasters in Iowa (!) is on NTI154] that played Midwestern Ramada Inn lounges.

"At this point it started getting really crazy, like heavy outfits and makeup. We were doing Boz Scaggs and Bee Gees, but we were also doing Kiss and Sweet and it was kind of a weird kind of a lounge act where we got fired for being too loud. We thought we were gonna make it! We had some amazing experiences where we would fill places and people saying this is the greatest thing that we've ever seen. It's almost like you're stars even though we know you're not because your van's parked outside and you're loading equipment in and out!"

And while Stevie was humping his gear, Ira Robbins was giving the commercially unavailable Phonography its first boost in Trouser Press. "It was late '77. I was on the road, Des Moines I think it was, and talked to Harry by phone. He said 'you gotta move up here.' And somehow I snapped and thought 'O.K., yeah, I'm gonna do it somehow. Pack up my car and drive up."

So in March of 1978 it happened. Harry fixed Stevie up with a sales-clerk job at Sam Goody's (the east-coast record retail chain giant) in Livingston, NJ, and a one-room attic apartment in Montclair. As Stevie acclimated to life in Northern suburbia, the endless creating/taping madness continued. This period of transition was marked by the release of a second album titled Delicate Tension, which offered the last of the Nashville recordings and the first batch of Garden State bounty, RSM style. Moore eventually found employment at Crazy Rhythms, a record emporium of note, also in Montclair. His digs and day gig remain the same to this day.

More Moore independent vinyl releases followed in the U.S. and overseas. Highlights of the RSM catalog include a 45 of "Goodbye Piano" (coincidentally and prophetically released by a small French company called Flamingo!), and LPs on the renowned French label New Rose. Glad Music (1986) was Stevie's first album recorded in a real studio. Everything You Always Wanted to Know About R. Stevie Moore But Were Afraid To Ask (1984) was a 36-track double set. The gatefold sleeve featured "In Fact, the Story of R. Stevie Moore," a praise-strewn "autobio." The essay was bylined with the good name of Robert Christgau, the opinionated and widely-read New York City music critic, but in fact these liner notes were ghost-written by a very brass-balled Stevie! Genuine press raves ran in the U.K. in Melody Maker, NME, and Sounds, while stateside support continued in Trouser Press and the Rolling Stone Record Guide.

He half-reluctantly played out a bit, gigging as a solo act or sometimes in various bands like the Biggest Names in Show Business [see NJ103], the Boxheads [see NJ46, NJ52, NJ61, NJ102], the Rayvens [see NJ90, NY97, NY98], and R. Stevie Moore's 3 Blazers [see NJ140, NJ147] with the musical and spiritual support of such Stevie-philes as Chris Bolger and Irwin Chusid, at N.J. venues like the Jetty (in Bloomfield) and Maxwell's (in Hoboken), and New York City's legendary Folk City.

And despite Uncle Harry's continual support and the doors that opened as a result of his ascendence into the ranks of major record label service, one plaguing question lingered (and remains to this day) where Stevie's unclassifiable music was concerned: what to do with it?

Was Stevie pleased with the way Uncle Harry rendered his work in the form of Phonography? "How could I not be? Then, as now, I'm real easy to please. I'm not that critical about how I'm presented. I've gone through the whole thing of 'please exploit me!' Steal my songs, I don't care. Twenty, maybe ten years ago, I've never cared about getting things copyrighted, and worried about people stealing ideas in songs. I wanted that to happen all my life. Now I'm thinking, well, you know . . . I just wanted somebody to pay attention, even if it meant artistic suicide."

Is it fun any more? Is R. Stevie content with his worldwide acclaim as a pop cult icon? No, in his own words, he is "pissed off" at his lack of success. "It feels like I'm still getting started, still being unknown, trying to break away from having a fucking day job."

Maybe the future holds a new world for R. Stevie Moore. Perhaps he'll someday fulfill his fantasy of recording an album with a different producer for each track. If some music-loving record company with decent distribution and muscle would do right by the man, all good music fans around the globe might get the opportunity to sample the outer strati of R. Stevie's far-from-depleted ozone. Maybe a crooner of note might choose one of our boy's more palatable tunes and hip the unconverted to the fold.

But maybe not. In an imperfect world, R. Stevie Moore reigns supreme. And possibly, the answer to all of this conjecture might just lie within his song "Why Can't I Write a Hit?" in which the artist responds to his self-posed title query with the line "your songs are too weird."

Yet hope springs eternal. Stevie continues to write and record daily with a ferocity unparalleled. He's still got the goods. And so do we. If all else fails, we can now hold the lovingly-expanded Phonography close to our hearts and digital reproducers.

-- Dennis Diken, 12/10/97