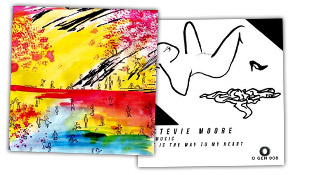

Lo Fi Hi Fives (A Kind Of Best Of) ~ R. Stevie Moore (6 AUG 2012)

Compilation with/by/for Tim Burgess, OGenesis Recordings OGEN 021 (UK) 2LP + CD

[01] Pop Music

[02] Show Biz Is Dead*

[03] Why Should I Love You

[04] Dutch Me**

[05] Big Mistake***

[06] The Winner

[07] Here Comes Summer Again****

[08] Hurry Up

[09] I Go Into Your Mind*****

[10] Another Day Slips Away

[11] You And Me

[12] Sentimental Ties******

[13] Little Man

[14] Find Any

with cameos by Irwin Chusid*, Ariel Pink**, Ray Carmen***, Billy Anderson****, Roger Ferguson****, Terry Burrows*****, Krys Olsiewicz***** and Lane Steinberg******

DIRECT LABEL ORDER INFORMATION > > 2LP VINYL | CD

R Stevie Moore ‘Lo Fi Hi Fives.....a kind of best of’

R Stevie is fast turning into a 40 year overnight sensation. A recent cover star of The Wire and a record store day split single with The Vaccines have meant that people want to know what R Stevie is doing.

For the last 4 decades, R Stevie has been making albums and creating an impressive back catalogue. That back catalogue consists of over 500 albums. The task of compiling ‘Lo Fi High Fives’ was something O Genesis supremo Tim Burgess had to keep moving on, sure in the knowledge that once they'd all been heard, R Stevie would have recorded another handful that would have to be pored over.

‘Lo Fi Hi Fives’ is just the tip of the giant foam finger, check out David Quantick’s sleeve notes below for a real flavour of the man. Add him on facebook. His back catalogue is best appreciated when he posts his songs and his own hipspeak messages. (OG)

(Sleeve notes)R STEVIE MOORE

“How much music can we take?” asks R Stevie Moore on the song 'Show Biz Is Dead', and it seems an odd question for this extraordinary artist to ask, for there can’t be anyone as prolific and as good as him working today. R Stevie Moore has a back catalogue that some record labels would be proud of, let alone some artists.

Since 1968, he’s recorded more than 400 albums and written enough songs to fill several festivals to the brim.

Another things that’s great about R Stevie Moore – apart from his name, which makes him sound like a robot in an Isaac Asimov novel, even though his music is far from robotic and emotionless – is that he doesn’t just write songs called 'Pop Music', he makes Pop Music.

There’s a kind of received truth that’s grown up in the last few years, that anybody who’s cool and underground (by which I mean that they don’t release their music through major labels or have blisterpacks of badges with their name on for sale in large music shops) isn’t supposed to make great pop songs, they’re supposed to sound clanky and bad and write songs on an old plank and live in a hedge. They’re not supposed to sound like George Harrison channeling Beck, or Cheap Trick remembering a Residents song they once heard on a strange radio, or The Beach Boys recording a session for John Peel in 1979. But that’s what R Stevie Moore is. He writes songs that should be, or would be, hits and maybe are in a distant galaxy. He’s a brilliant songwriter and he doesn’t bury his talent in the shed gunge of deliberately bad production; these are songs which sound as good as they ought to, at once both smooth and hard, shiny and gritty. It takes brilliance to do that.

You can hear the people who R Stevie Moore has listened to in his music – or at least you think you can, for all we know he’s never listened to any music in his life and is just making it from inside his extraordinary mind – but that doesn’t mean R Stevie Moore is one of those people who take bits of pop and rock that have gone by and glue them together to create something ironic or Frankensteiny. This is music that you have never heard anywhere else other than on a record by R Stevie Moore. This is an original voice – literally. If you have everything by R Stevie Moore already, then you probably are him. If you don’t, this is a wonderful collection and you should put it in your music system, your car, your heart and your mind. This is Pop Music like you have never heard it.

DAVID QUANTICK, 2012

|

THE GUARDIAN by Tom Hughes guardian.co.uk, Thursday 9 August 2012 R. Stevie Moore Lo Fi Hi Fives..... A Kind Of Best Of ★★★★★ (5 stars)

Despite being, in a sense, born into the US music industry – his father Bob was one of 50s/60s Nashville's top-tier session bass players – R Stevie Moore has spent his strange and rather wonderful career firmly outside it. Since 1968 – and to this day – he has been busy in his basement home-taping an endless stream of eccentric, off-brand pop, apparently trying to copy the hits he heard on the radio and getting it all just a tiny, lovely little bit wrong. Much of it is utterly lo-fi and wildly, kaleidoscopically elaborate at once, and this terrific compilation herds together some highlights of his unknowably vast discography (by some counts more than 400 albums strong). And there are real treasures here, from the thrumming, Neil Youngish The Winner to oddball power-pop gem Why Should I Love You? (recently covered by the Vaccines). An outsider hero whose cult seems to keep growing with each generation, Moore could hardly be a better advert for going your own way.

. . . . www.guardian.co.uk/music/2012/aug/09/r-stevie-moore-lofi-review

PITCHFORK REVIEW, by NICK NEYLAND

A thread that ran through The Wire's recent cover feature on R. Stevie Moore highlighted how often the singer has battled against preconceptions formed about his music. The "lo-fi" tag is often attached, even though many of his best recordings purposefully battle against the kind of tape-recorder grime the likes of Guided by Voices deliberately wield as an aesthetic tool. Moore also commented on how little he had in common with "outsider artists" with whom he is constantly bracketed, giving a nod to the talents of Wesley Willis and Daniel Johnston while highlighting how his skills as an arranger put him in a different league. In fact, as Wire writer Matthew Ingram asks: "Why is he in the 'weird' camp at all?" Part of the reason is the 400 or so albums he's released since the late 1960s, coupled with the fact that he's still working at a prodigious rate despite turning 60 earlier this year. Anyone attempting to find an entry point into his work would be forgiven for feeling over-awed by the sheer breadth of it-- something this compilation seeks to address.

Moore was born the son of famed Nashville musician Bob Moore, who counted gigs as a sideman for Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, and Bob Dylan among his towering achievements. His uncle, Harry Palmer, is best known for discovering the ultimate outsider music act, the Shaggs. It's difficult to sum up the work of a man with so many recordings to his name, but somewhere between father and uncle lies Moore, pulling in pure pop influences and rinsing them through his off-center take on the world. For a long time it looked like he would be perma-bracketed as a musician's musician, the type of guy feted by other artists but barely known to the outside world. Ariel Pink has been Moore's most famous cheerleader, but dig a little deeper and you'll find collaborations with Jad Fair, Mike Watt, and MGMT among others. Tim Burgess of the Charlatans, another former collaborator, has issued Lo Fi High Fives on his O Genesis label, making it the latest in a string of compilations (including the Pink-curated Ariel Pink's Picks Vol. 1 from last year) that attempt to make sense of his greater body of work.

Except, of course, this is a pebble skimming across the surface of that output. There are few signs of Moore's excursions into rap, post-punk, metal, or techno. Instead, the dial twitches between his knowing take on pop and his fondness for Ween-style prankster rock. Sometimes those two worlds collide, most often when Moore draws his audience a little too close to anything that could be marked as "sentiment." On "Find Any" he sings of being "sick of singing about girls because I can't find any." But Moore tempers the feeling by turning the lyric into feeling "sick of singing about cats because I can't find any," complete with screeching "miaow" noises. Such lyrical rug-pulls are commonplace in Moore's songs, and may partially explain the disconnect with a wider audience. Just when it feels like you can lean in to get close to him, he's ready with the songwriting equivalent of one of those flowers that clowns use to squirt a jet of water into your eye.

Humor is key to Moore's arsenal, although much of his musical inspiration is drawn from a string of artists who are a lot more at ease with laying themselves bare. The influence of Brian Wilson and the Beatles figures prominently on Lo Fi High Fives. "Here Comes the Summer Again" is a note-perfect Beach Boys pastiche, while the more impressive "I Go Into Your Mind" channels both "In My Room"-style melancholy and the haunted Disney fantasiasMercury Rev were chasing circa Deserter's Songs. On the opening "Pop Music", Moore wraps his singular commentary on pop around playing that combines shades of "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" with the pomp of ELO and subtle honky-tonk piano stabs. All of the above help back up Moore's claims for his skills as an arranger, but it's when he steps away from self-consciously aping pop history that his work finds its unique depth. On "Big Mistake" he sounds genuinely lost and confused by the world, digging hard into the feeling of being cut adrift from his peers and the public for so long. A yearning for wider acceptance creeps into his most impressive work, a sense that he's drawing on the unusual energy created by releasing song after song into what must have seemed like a total void.

But that's only a fraction of Moore's story, as told by this album's diversions into power pop ("You and Me"), scruffy psychedelia ("Sentimental Ties"), and the hollowed-out Ariel Pink collaboration "Dutch Me". What's remarkable about Lo Fi High Fives is how instantly familiar much of this material feels. Partly that's due to Moore's ear for emulating the songwriting techniques of others, but he has a way with song structure and melody that makes it feel like some of this stuff has been floating around in the ether forever. "Why Should I Love You" is so brilliantly simple and catchy that it has "hit single" written all over it (and, indeed, others have felt the same way). It's hard not to wonder what the cumulative affect this whole process had on Moore's psyche-- Pink wrote some pop gems early in his career ("Helen", "Alisa", "Every Night I Die at Miyagis") but subsequently stumbled into success. Moore remains lodged in a gap somewhere between tiny personal victories and an utter failure to connect, and it's in that tension that he produces his best work.

Why are we so drawn to someone like Moore, whose catalog is too vast for even the most ardent fan to fully grasp, who seems intent on throwing myriad curveballs in our path just when we think we're getting to know him? The reason, at least in part, is that it's a disarmingly honest way to operate. Not everyone can go down the route of, say, Lou Barlow or Elliott Smith, who were both capable of delving into an alarmingly personal train of thought every time they stepped up to a microphone. Moore has elements of that for sure, but he's also unafraid of coming across as clumsy, confused, perhaps even a little shy. There's value in expressing the feeling that occurs when you pull back from the brink by telling a dumb joke just when you think you've said too much. And Moore has arguably said more than most. Tales of artists who never got their dues are legion, but Lo Fi High Fives does enough to suggest that Moore deserves a place near the top of that particular pecking order. Thankfully, he's still out there. A new album already tucked under his arm. A dreamer, still dreaming. http://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/16959-lo-fi-hi-fives/

BBC Review

LO FI HI FIVES

The back catalogue of 60-year-old Robert Steven Moore makes Guided by Voices look like Kate Bush by comparison, and Ariel Pink as idiosyncratically weird as Cliff Richard.

Moore has released between 400 and 500 – no one really knows – cassette and CD-R albums. This, amazingly, doesn’t quite equal the prowess of his dad, Nashville session veteran Bob Moore, whose CV includes Elvis Presley and Roy Orbison.

Stevie’s talents are more, ah, eccentric (check his Wikipedia photo, a front-combed grey explosion). One reviewer bore witness to “an outrageous collection of musical brain spewage," though this one-man-band (he plays guitar, bass, keyboards and percussion) is probably a lot more proficient than you or I.

Cherry Red has released two compilations before, but this collection (from Tim Burgess’ O Genesis label) comes on the back of this year’s Record Store Day single: Moore covered The Vaccines’ Post Break-Up Sex, they in turn covered Why Should I Love You?, a neat slice of surf-power-pop included here.

It’s one of the tidier ditties, alongside the Casio chug of Dutch Me and the broody, oddly moving Big Mistake. But even when he’s tidy, there is a sense of something wobbly, something not quite right, as if Moore was recording after 48 hours of no sleep.

Here Comes the Summer Again, for example, nails what David Quantick’s sleeve-notes describe as George Harrison channelling Beck, Cheap Trick remembering a Residents song once heard on a strange radio, or a Beach Boys’ John Peel session. All are valid comparisons. Pop Music is well titled, with blended horns, but it’s a bit Syd Barrett-y and the guitar solo is bendy. Little Man’s chord progressions feel very ELO, but would Olivia Newton-John want to sing it?

Moore’s favourite default position is a style of subterranean AOR, with guitars flanging and tripping the light fantastic. On a very lo-fi budget. So God bless the person who had to cherry pick these 14 tracks. Lo Fi High Fives all round. Meanwhile, his Wikipedia page says Moore has plans for more recording projects. Stevie, you surprise us.

Dots and Dashes . . . - - - REVIEW:

The most prominent concern with any LP from the harebrained, messily haired wizard of lo-fi, R. Stevie Moore, regards his ability – or lack thereof – to hold the thing together across a more comprehensive tracklisting. I mean Moore's had more than enough practice in honing his craft (Lo Fi Hi Fives is his latest UK release in an uncountable album inventory of hundreds) yet bizarrely although it may serve as something of a greatest hits, it's arguably his most coherent collection ever outed. Dubbed A Kind Of Best Of and compiled by none other than Tim Burgess, Lo Fi Hi Fives has Moore washing his hands of the scatological nonsenses splattered across the archives in favour of song. A phenomenon which here feels slightly strange in itself, but as soundly as lunacy befits Moore these here melodies will surely have ever more acolytes humming his praises. They're now overtly hummable for the most part, and contextualised by the humility of the reclusive whiz the record becomes not a semiquaver short of exultant.

Although he may have been endowed with a preternaturally deft ear for sumptuous mellifluousness (that his collab with the garrulous Ariel Rosenberg be polemically entitled Ku Klux Glam yet not only become culturally acceptable but also highly affable to ears inundated with wave upon wave of indiscernible blog ebb ought attest to that) it's hard not to feel as though his talents have oft been spurned in favour of concerted subversion. Inevitably Moore here goes for a few Hi Fives which land a little awry: the dark Salford synthpop slump of Big Mistake grates as much as the segueing acoustic meander of The Winner is incontestably great, whilst his scruffy lamenting of a lack of "girls", "love" and "trucks" in life on Find Any takes the Lo Fi vibe to an unendurable extreme. Chugging through the gears of condensed buzz saw guitar and synths picked up from the Pet Shop Boys' flouncy storefront, the latter provides an arresting ending to this compendium of sorts yet it's one you wish would truck off a minute or so into its protracted, gruesomely repetitious four and as Moore quizzes on another inexcusably scrappy track called Show Biz Is Dead: "How much music can we take in terms of running time?" he here overruns, hereby answering his own quietly self-effacing inquisition. Exhibitions of sanity slipping through Moore's curled fingernails these may be therefore, but there's tunage worth grappling with and grasping if possible among the maddening mêlée.

Whether that be the ELO-esque histrionics of retrospectacular opener Pop Music which is, joyously unashamedly, just that or the thunderous jitter to Hurry Up which arouses midway through the overall running time like a Sebadoh-stained wet dream atop Pontins bunk, Moore's indisputably got it. I mean he's seemingly lost it, although musically? It's wondrous stuff. The synthetic flutes of I Got into Your Mind kiss trip hop snares and strings so rich you sense they could only possibly be sampled in an amalgam that's as though Millennium-turn F'Lips smooching with The Avalanches whilst the Antipodeans swipe The White Album. The intoxicating fumes of Rosenberg's Haunted Graffiti get all up in Moore's grill on the peppy Why Should I Love You and rather more placid, euphemistic Dutch Me. Little Man then scintillates as though a perfectly formed pop nugget excavated from Zager & Evans' glinting trove now inhumed in time. Thus late '60s and early '70s referencing becomes pretty omnipresent, and indeed Moore irrefutably belongs to another epoch. Whether that be one indexed in any old clunk of history textbook is rather less conclusive although textbook is precisely what the breezy vibes to Here Comes the Summer Again seem. Moore's studied infatuation with The Beach Boys here forever incarnate in a gooey blur of retrospection as indebted to Smile as it is to N64 soundtrack ensnared in plastic cartridge, these be minutes worthy of dissertational explication.

Similarly, the dichotomy between Daniel Johnston-styled sketch (the both gawky and Gorky's Another Day Slips Away) and downright sketchy (the ludicrously curt ending to the Lemonhead-scented rollick of You and Me, say) is one worthy of footnoting although essentially, Moore ought now be appreciated and with it admired as is Johnston as a tutor of his beloved Lo Fi. Stick this one in your Pitchfork and smoke it 'til helplessly stoned then, yeah?

www.dotsanddashes.co.uk/2012/08/smokin-r-stevie-moore-lo-fi-hi-fives.html

THE QUIETUS The inherent difficulty with writing about outsider music is that taking a song, an album, or a live show on its own terms becomes next to impossible. It's a paradox: very often the art is made in a way that seeks to slip the net of mainstream relations of production and distribution which stress extra-musical irrelevances, but this choice itself diverts attention back towards the productive process rather than the music. As a result, the debate around the subject ends up focusing on tangents, especially the question of which criteria should be used to define an 'outsider' in the first place. Broadly, though, the vast majority of the outsider music encountered by anyone likely to be reading this will fit one of two categories. The first might be epitomised by someone like Jandek. It rejects industry standards of listenability – melody, harmony, tuning, clarity of recording, emotional coherence – to produce artefacts which undermine conventional wisdom about the desirability of those things and, in doing so, reveal the act of social construction by which 'music' comes to be identified in the first place. Opposed to this one finds musicians who, rather than being alienated by what they encounter on the radio, are moved by it to the extent that they refuse to allow it to be mediated on their behalf by conventional channels of distribution. This notionally 'pure' pop music is what R Stevie Moore has been doing since the late 1960s, although it's only recently – thanks in part to the attentions of outsider-aping insiders like Ariel Pink and John Maus – that he has broken cover. Having not taken a great deal of notice of Moore's emergence, this is my first real meeting with his work, and, listening to it, I feel a little as if I've stumbled into pop music's uncanny valley. All the tropes of American AM radio from 1960 through 1980 are there, and mostly in the 'right' places, but it's precisely the slightness of the discrepancy between what Moore does and the commercial artists he responds to which makes his work so radically different from theirs. It's as if someone has broken into your flat and moved every object on the walls a few millimetres to the left, coincidentally into the places in which they should probably have been in the first place. Perhaps I'm speeding ahead of myself a bit here. Perhaps I'm assuming that you're a bit more up on this than I am, and that I should have stated earlier on that Lo Fi Hi Fives is a 'best of' Moore has compiled with the assistance of fan and O Genesis head Tim Burgess. Perhaps, though, I've got licence to write candidly about being a newcomer to this, because this album might very well find its way into a lot of ears similarly lacking in previous exposure to Moore, ears belonging to people who are going to spend a substantial amount of time trying to figure out what it is that's so peculiar about his music. Better, maybe, to try and describe this strangeness, or these strangenesses, than to talk about whether or not this project works as an adequate reflection of Moore's body of work. It might be the utopianism. Moore and Burgess have chosen to open the collection with 'Pop Music', one of those meta, Lou Reedian statements of allegiance to the transformative power of the radio. The gesture reminds you that this is the handiwork of someone liberated from cynicism, of an individual singularly determined to make pop music according to their own interpretation of its charter. Of course, there are artists who stand just on the industry side of the border between insiders and outsiders – Super Furry Animals, The Flaming Lips, Guided by Voices – similarly guided by the notion that only musicians and fans (and certainly not A&R or marketing) truly understand what pop music should and can do, but their decisions can only be laudably 'brave' defials of commercial logic rather than the truly free acts they aspire to. Moore, superficially similar both melodically and in terms of arrangement to all of the above, has worked genuinely unencumbered by any form of answerability and it shows. Over and over again, he ignores commonplaces about what 'works' in favour of a song's internal requirements, meaning that solos end up much longer or shorter than one would expect, refrains outstay any welcome a label-hired producer would be willing to extend, and instruments drop into the mix unheralded to play distracting countermelodies which are, nevertheless, sheer expressions of the pleasure to be found in making. In Freud-speak, Moore is the id of pop: his songs are collages of the pay-offs of others shorn of legwork and deference. Like those trompe l'oeil Sunday dinners you find in sweetshops in Blackpool or Scarbrough, even the cabbage turns out in the end to be candy. The risk might be that such an approach flattens music into a white-out of 'good bits', but Moore's melodic nous is far too sharp to allow that to happen. 'Dutch Me' – its title arguably a pun on the mainstream's representation of sexual neediness – works Walker Brothers-like romantic angst through a clip-clopping beatbox and various echo units into something one could reasonably describe as a brilliant soundtrack for a terrible night in Las Vegas. Right on its heels, 'Big Mistake' extrapolates the augmented chords pop is supposed to leave to its muso antagonists into something alternately spooky and plaintive, before cutting it apart with bizarre half-bars of busy folk-rock reminiscent of Pentangle or Fairport Convention. 'Hurry Up' is a Joe Jackson song unbound, while 'You and Me' appropriates Lennon-McCartney harmonic cunning to the cause of bedroom recording in a way which aligns Moore to GBV's Robert Pollard. With Moore, it's possible to write about the music and the eschewing of standard productive processes at the same time, for the very reason that his songs so often seem to be correctives to those moments in which pop has failed by trusting its market research over its instincts. Each track here is like a counterfactual history of a style, a nod to what might had been, had those put in charge of commercial music's dissemination not been so frightened of making mistakes. I'm not personally convinced by the presentation of Moore as an icon for the contemporary avant garde – the Wire cover still strikes me as strange for the same reasons that I don't really believe Ariel Pink – but he's certainly capable of telling a better story about the past than the normal hagiographies are. thequietus.com/articles/09636-r-stevie-moore-lo-fi-hi-fives-review The Line Of Best Fit Looking back at the colourful cavalcade of cartoon images from the rose-tinted living room of your early life you’ll often find that there was, perhaps, a lot more going on within the realms of Saturday morning cartoons than your young eyes were able to perceive at that time. It’s an old cliché that adults watching kids’ TV will remark as to the volume of drugs the writers must have been on when they committed ideas like Ninja Turtles and space-bound hares to paper, but it also holds some truth. The brain on drugs is much like the brain of a child – you’ll notice similarities between the behavioural patterns of a guy on a ton of MDMA and a lil’ brat amped on aspartame. Cats in orbit is a fine idea both to little ‘uns and wreckheads. Where’s this all going? You may well ask. R Stevie Moore is here to tell you where. Nowhere in particular I’m afraid but as long as it feels right, or half-right or failing that, downright warped and weird, it’s probably a semi-coherent metaphor for his music. Moore is, when we break it down, the audio representation of the moment when you come of age during one of those psychedelic cartoons. He’s the clown with a hand on your shoulder for one of two reasons. Maybe three. Moore has, we must trot out, released upward of 400 albums via the media of vinyl, tape, CD-R even VHS tape over the last near-forty years. Tim off of The Charlatans loves him (and is in fact releasing this on his own label); he’s been embraced as a counter-culture something-something by whomever in New York and, well, after many years in obscurity, his star is beginning to shine a little brighter. This is delightful news for an extremely willful and exotic character with a shard of brilliance dug deep into the pleasure centre of his left brain. This “best of” – there are no hits to speak of so they’ve kinda plumped for the most commercial-sounding ones – is a brief toe-dip into the animated world: imagine yourself as the blonde girl from Poltergeist staring into that fucked up TV and pushing a finger through into the beyond. Here we have a clutch of lean-to pop songs like opener ‘Pop Music’ – an AOR tune fed through an infant’s sensibilities and David Baker delivery. It’s a faxed, photocopied and hand-altered version of mainstream music with all its darkest corners highlighted garishly in marker pen. There’s the proto-electro of ‘Dutch Me’ which shares some lyrics with A-Ha’s ‘The Sun Always Shines on TV’ and conjures a momentary but wonderful image of Moore and Morten Harkett switching careers. He woulda been great on Going Live! Here Moore’s voice, as it often does, wavers wildly, wandering across octaves, unsure of where it wants to be before jerking into a bluesy growl. As on several of the tracks the combination of blind repitition and sudden, jerking left turns is unsettling but unquestionably original. The fact that many of the choices here paint Moore as a kind of burned-edge facsimile Randy Newman gone twice through the psych shredder does little to dispel the faintly queasy nature of the work. There are so many more baffling ‘pleasures’ here. The bubblegum power pop of ‘Why Should I Love You’, spurting and sicking up Raspberries melodies over Gruff Rhys’ shoes; ‘Showbiz Is Dead’ – a squelching, shredded VHS version of experimentia with a shoegaze guitar tucked under its arm and the telling line “Look at me singing a song/It don’t sound like any other”. There’s also the beaten Joy Division beauty of ‘Big Mistake’, all rumbling bass, illogical chord progressions and fleeting transcendence, and the bedsit epic ‘I Got Into Your Mind’ – a restless sleep of a song that raises a notion of Wayne Coyne at his most human, his least bombastic. “Your brain wants/Your brain gets” he breathes, a bed-ridden barbiturate Bowie. When it moves into near-Massive Attack breakbeat it nearly brings a string induced tear to your squeegeed third eye. There’s even more confusing, hair-raising gear here too – like the magled TDK90 of ‘The Winner’ – surely a Graham Coxon fave, or ‘You and Me’ which takes the basis of ‘Twist and Shout’, twists harder and swops the shout for an atonal, heavily-accented horn of a voice dropping sweet/dumb platitudes like “I love you and I miss you” as if trying to disguise itself as part of the legit genre rather than a funhouse mirror reflection of the same. A key thing: he doesn’t reach out to grab you necessarily, you have to meet him halfway. As colourful and vivid as some of his material is, it’s still somehow insulated, separate and at a slight distance from “casual” listening. Among the tougher trawls are the ominous ‘Hurry Up’ – the sound of a garage band drugged to the point of collapse but still fuelled by frustration – and the almost-emo (yep) of ‘Sentimental Ties’. There’s even a horrid nod to classic rock on ‘Little Man’, all complex metallic riffing, laser beam effects and bullshit lyrics. Urgh. These are the aftershocks of modern music, ya know? The disturbed reverberation of the colour and sound that push into the mind through radio and TV over a lifetime. They’re out there on another plane with the poltergeists. Moore is up there with the space rabbits, in the sewer with the mutant turtles and all over everywhere else magpie-ing ideas and concepts, allowing his warped thoughts to turn into half-lit dreams. Anyway, get to youtube and watch all of his amazing homemade videos. Then buy his debut proper (Phonography) and then get this to win over your mates with. They may think you’re fucked on drugs, but they may also think you’ve found your inner cartoon kid. And we all need one o’ those. www.thelineofbestfit.com/reviews/albums/r-stevie-moore-lo-fi-high-fives-102658

Loud and Quiet album review

MUSICOMH There's something of the hoarder to R Stevie Moore, a man who piles stuff in unsteady towers, stuff that dominates his house, to the extent he's in real danger of immolating himself every time he switches on his hob. And by house, we mean mind. And by stuff we mean ideas. You can hear a lot of those in Lo Fi High Fives. Nothing sticks around for long. Some is good; some is bad. None of it is ever boring. So who is R Stevie Moore? Well, he's a man. With a beard. An astonishing beard. The kind of beard that makes his face seem like an afterthought. And he's someone who puts the pro in prolific, producing something like 400 albums in a 40-year career. To put that in perspective, if Mumford And Sons are planning a similar level of output, then, based on their current work rate, we're going to have to put up with them for the next 1000 years. Sigh a lot more. Moore is also a 'lo-fi legend' who is on the verge of becoming a lot more famous. Recent high profile patronage from Ariel Pink and Moore's O Genesis label boss Tim Burgess, and a single with The Vaccines, and suddenly people are interested. For many, Lo Fi High Fives will be an introduction; an attempt to provide a taste of some of the guises that Moore has taken over the last four decades. It begins with the recent (and lovely) Pop Music - think Beck covering Waterloo Sunset. Then we drop back three decades to 1981 for Show Biz Is Dead – think a new-wave, post-punk strut like Talking Heads. Then we zig forward to Why Should I Love you from 1986 – think jittery dynamics and surfy guitars that could easily be a lost track off Surfer Rosa. Then, think you should have a rest. Three songs. Thirty years. Three totally different sides. Do they make sense together? Sort of. There are some moments of commonality throughout proceedings, and themes which recur - a Beach Boys fixation is one, a Beatles-esque way with a harmony is another - but more often than not the tracks of Lo Fi Hard Fives are baffling non-sequiturs. Not that you'd imagine Moore gives a shit. Which isn't meant to suggest that he doesn't care. In fact, if you were looking for someone to prove that lo-fi, DIY doesn't necessarily mean careless, you can find are plenty of examples here (Big Mistake; Here Comes The Summer Again; I Go Into Your Mind). It's more that he has been dancing to the beat of his own drum for so long that you guess he's happy doing his own thing. Something which makes the 'outsider artist' label he's been branded with seem appropriate. But when listening to Lo Fi High Fives, the tag jars. Yes, R Stevie Moore has followed his own path, free from commercial boundaries, but he's not done so in a vacuum. He hasn't been unaffected by the mainstream. But, that's ultimately kind of moot. Regardless of whether this is the start of the outsider being brought inside or not, Lo Fi High Fives is a weird, engrossing, often totally brilliant representation of a singular musician. www.musicomh.com/albums/r-stevie-moore_0812.htm

SOUNDSXP Article written by Ged M - Aug 25, 2012 A Trouser Press review in 1976 described Robert Steven Moore’s first album as “an outrageous collection of musical brain spewage” and thirty-six years and 400+ releases later, this is still true. He’s the poster boy of outsider music, constantly home-recording music and releasing it through a plethora of labels or on his website (over 200 downloadable albums). Now championed by Ariel Pink, the Vaccines - who released a split single on Record Store Day with him - and Charlatans’ Tim Burgess, whose label is releasing this compilation, he’s receiving serious attention at last. Working in a record shop, and the son of a Nashville musician, he’s absorbed countless influences and synthesised them in his songs but, rather than replicate, everything is a slightly woozy version of something else, as seen through the RSM filter. ‘Pop Music’ is a George Harrison tune with blasts of brass and ‘Big Mistake’ like a narcotised Nirvana just before submitting to oblivion. ‘Another Day Slips Away’ is the sort of whimsical psych pop that Andy Partridge has been fooling round with for decades while ‘Here Comes Summer Again’ is a crude copy of the Beach Boys, deadly accurate in its elements but a bit off in execution. It’s very well recorded (the “lo-fi” of the title misleads) but it’s not surprising that he’s always occupied the periphery. He has quotable lines for reviewers (“how much more music can we take?” he asks in ‘Showbiz is Dead’) and he has reportable collaborations (although ‘Dutch Me’, his co-write with Ariel Pink, is fey New-Romantic nonsense) but effectively this is musical painting-by-numbers on a huge scale. Fun and listenable - the raw powerpop of ‘Why Should I Love You’ stands out - but this is the very definition of cult. www.soundsxp.com/artman2/publish/albums/R_Stevie_Moore_Lo_Fi_Hi_Fives.shtml Boomkat Product Review: It's been great to see R. Stevie Moore getting some long overdue recognition of late - the subject of a recent Wire cover feature and recipient of lavish praise from relatively young pups like Ariel Pink, John Maus and MGMT, all in thrall to his mastery of DIY popcraft and ebulliently don't-give-a-f**k attitude. The generously bearded Nashville eccentric has recently fallen into the orbit of Tim Burgess's thriving O Genesis label (which brought us that recent Nik Colk Void single), and having already furnished the imprint with a couple of 7"s, he now throws open his back catalogue - spanning 35 years and hundreds upon hundreds of songs - for Burgess to assemble a "kind of best of" available on vinyl and digital. A leaner, more accessible selection than Ariel Pink's uber-limited cassette comp of last year (Pink's Picks), Lo Fi Hi Fives demonstrates exactly why RSM is held in such high regard: for all the talk of DIY and lo-fi, the songs Burgess has zoned in on are beautifully composed and recorded, with a clarity of sound and richness of instrumentation that any big-league studio would be happy with: check 'Pop Music' and 'Why Should I Love You', the former a sulltry, brass-inflected psych miniature, the latter a zinging power-pop anthem that once in your head, will never, ever come out. More eerie constructions like 'Big Mistake' and the drum machine and synth-led 'Dutch Me' hint at a darkness latent in the otherwise ostensibly sunny Moore worldview, while 'Here Comes Summer Again' deserves special mention for attempting to pastiche Pete Sounds and succeeding - with glorious harmonies and a twinkling arrangement that'd make Brian Wilson proud. Twisted humour, old-fashioned romanticism and an unflinching belief in the power of song to make sense of life: these are the things that make R. Stevie Moore great, and they're beautifully represented on this unmissable compilation. If you're new to his work, it really is the perfect introduction. http://boomkat.com/vinyl/545287-r-stevie-moore-lo-fi-high-fives-a-kind-of-best-of FACT MAGAZINE 14 AUG 2012

R. Stevie Moore: Lo-Fi High Fives This month’s Wire cover star, for some years now R. Stevie Moore has been pimped around the egg-head scene as a master conceptualist. Not least by Ariel Pink, Moore’s devoted disciple and now collaborator. Unlike with Pink’s music, however, conceptualising the 60 year old’s bedroom-produced pop feels like an act of intellectual self-delusion. And not because it’s nigh on impossible to do your po-faced theorising to the sound of distressed jizz-cats – as which lines the feline-sampling, frantically frustrated sex song ‘Find Any’. If Pink is knowing, Moore is unknowing. One is active, the other passive. Pink was fully aware he was playing deconstructionist, when over a decade ago he began toying with pop presentation in a completely unprecedented fashion. Rather than just a matter of scuffing-up random esoterica, Pink’s music succeeds in channeling the “fading cry” he claims to have “heard” as a child: the cry that echoed from pop as music’s golden age died in the late ’70s. Deceptively tricky to calibrate, this uncanny quality of cultural deja vu coded in Pink’s music – not quite nostalgia music, not quite pastiche, not quite dream-music – fully warrants the deluge of blog-academic discourse it’s inspired. Not only for its salience in the digital era and the ongoing “flattening” of time, but for the idea of memories as visions of the now dead. Moreover, like the music of nearly every art act in history – from Roxy to Scritti, Hype Williams to James Ferraro – Pink’s material is constructed in such a way that it’s made whole only when complemented by analysis. As Chuck Palahniuk once wrote, “where would Jesus be if nobody had written the scriptures?” This might just be the most narcissistic justification ever given for music criticism. In contrast, Moore’s music defies intellectualisation. He fetishizes pre ’80s music as the last epoch before pop became self-conscious; a phenomenon arguably catalysed by post-punk era music writing. He resists the house-of-mirrors anxiety that accompanies the type of pop which thinks to itself in a state of artifice. His approach to pop is obliviousness, something which descendants like John Maus negate with joy-killing analysis, talking in intellectualised Moore-isms throughout “simplicity is beauty” polemics like ‘The Truth of Pop’. But for Moore’s part he remains an innocent, forever chasing the insentient serenity that defines ’60-’70s pop: music divested of the art “devices” which the intelligentsia claim riddles his material. Predating Marcus-esque rock writing (Moore’s been recording since the ’60s) his music was never designed to be understood only by contextual extrapolation in the pages of mags like The Wire. Instead Moore shields himself from self-awareness. He’s an escapist and a romanticist, as opposed to a conceptualist. Sure, his songs are meta: appearing here, ‘Pop Music’ is a pop song about pop, for example, while ‘Show Biz Is Dead’ and the line “How much music can we take?” speak for themselves. But what his songs are not, are “essays on the form”. If the content is self-aware – a product of Moore’s eccentricity or too many years spent in his own company – the form isn’t. Moore doesn’t make “choices” or use devices. If Pink borrows elements from his music it’s the tone, not the concepts. The 60 year old is not the godfather of hauntology, he’s the beloved kook whose TV-Tommy grip on reality and post-ironic charm the hauntologists use to blueprint their skewed pop. It’s on ‘Big Mistake’ that this album really consecrates Moore’s final rejection of real life. The compilation’s highlight, it’s a prayer for the safe return to suspended animation. “Take me back to fantasy, I don’t want to know” he coos, before sinking into the simultaneously anaesthetized and distressed coda with a key-warped “This is impossible”. Away from the b-movie psyche-rock of ‘Hurry Up’ and ‘Little Man’, Moore shares Mercury Rev’s talent for rendering psychedelia the saddest music ever conceived. If his limitless passion is ever apparent, equally as palpable is a sense of his abiding isolation. All things considered, much of Moore’s mystique derives from the standard charms of lo-fi music and the beauty unique to amateurism. Like the music of Guided By Voices his songs cut with jarring efficiency between mini-events. They play like condensed clusters of Moore’s best hooks, as he implements his every idiosyncratic thought instantaneously and free of prudent commercial editing. It’s a refreshing air of spontaneity (see again GBV) compounded by Moore’s tendency to channel-surf through genres across the course of an album. His records play like an attempt to recreate the joy of flipping through stacks of obscure vinyl, and the thrilling promise of stumbling across a killer pop song amongst the heartfelt failures of some long forgotten band of dreamers, too weird to ever make it. His albums are all about discovery, while the sheer volumes of releases appeals to the record store loners and their compulsion to collect. And as is the case with Dan Treacy or Daniel Johnson, there’s the romantic and simultaneously heartbreaking notion of a misfit amateur making music for the pure joy of it, without hope of resolution. This is the dreamy, forlorn yearning of an unnervingly strange man, which Pink then conceptualised and duly mistranslated as retro, filtered through the unnerving strangeness of sad childhood memorises of a pop era that still sold us dreams. But Moore’s remorse has been, since 1966, lived in real time, not retroactively. He isn’t remembering, repurposing or defamiliarising, he’s just stuck. In fact, he is forgotten. Though he’s the original practitioner and both the sub-genre’s most otherworldly and most dazzlingly music-literate, fundamentally what we have in Moore is an honest-to-goodness lo-fi eccentric. It’s an interpretation of the artist which curator Tim Burgess is nudging us towards here, editorialising a relatively straightforward version of Moore by focussing on his most coherent, melodic, fully formed and accessible songs, while censoring his more tricksy efforts (which incidentally makes for the perfect starter pack for newcomers). Like John Grant’s headily melancholic Queen Of Denmark, ‘Pop Music’ emanates from the post-glam end of mid-’70s soft rock, channeling all the claustrophobic magic of America’s great suburban teenhood. The arrangement – a deft balancing of piano, trumpet and glitzy guitar – demonstrates a level of artisanship which, for what it’s worth, is beyond Ariel Pink. Moore balks at the label “lo-fi” for its associations with poor quality musicianship (he prefers “DIY-fi”) and it’s easy to sympathise given how accomplished many of the songs are on Lo-Fi High Fives. Interspersed between slipshod garage rock (‘Sentimental Times), crappy drum machine balladry (‘Dutch Me’) and TVP-esque proto-indie (‘The Winner)’ are tracks like ‘I Got Into Your Mind’ and ‘Here Comes The Summer Again’. The former begins with organ dabs a la ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ before blossoming into a majestic second half of hip hop-like beats and easy llistening strings. The latter, meanwhile, is the classiest Beach Boys facsimile you’ll hear all year – a perfectly structured, perfectly pitched slice of Cali paradise, sporting the evergreen middle eight of a lifelong Wilson fan. Then there’s ‘Why should I Love You’, another deftly constructed pop song that flits between verse and chorus, swinging sixties London and 70′s So-Cal, with consummate ease. And ease is the key word here. The ease of life adrift of the modern condition and all attendant academic critique. John Calvert www.factmag.com/2012/08/14/r-stevie-moore-lo-fi-high-fives/ UNCUT 7/10

R STEVIE MOORE

Tennessee lo-fi pioneer's 500 albums, condensed

EXTRAS: None.

|